Lessons from the Past: Reading, Writing, and Family Records

Lessons from the Past: Reading, Writing, and Family Records

Introduction

The smell of sharpened pencils, the scratch of chalk on a board, and the thrill of mastering the alphabet—reading and writing have always been at the heart of education. For genealogists, those same skills are essential tools when uncovering family history. School may have taught us grammar and penmanship, but genealogy asks us to revisit those lessons in new ways: deciphering fading handwriting, interpreting unfamiliar terminology, and piecing together the stories hidden between the lines.

Our ancestors left behind more than names and dates. They left us their handwriting in letters, diaries, and legal records. They revealed their literacy—or lack of it—through school registers, signatures, and even census responses. And they gave us clues about their world through the words they chose to record. If history class was about learning from textbooks, genealogy’s reading and writing class is about unlocking the voices of the past.

Among my grandmother’s papers were handwritten letters she had received, copies of poems, songs, recipes, knitting patterns, and stories she had admired as a youngster. I giggled at the letters, laughed at the poems, and even managed to decipher her handwritten knitting pattern for a baby shawl she had made for her children through to her great-grandchildren. Making the dishes and recreating the shawl connected me to her in ways no textbook ever could. These meaningful mementos are treasures I can now pass down to my own children, carrying forward traditions and stories that might otherwise have been lost and in her handwriting.

The Significance of Literacy in Family History

Not every ancestor could read or write, and that fact alone tells us something important. A missing signature, replaced with an “X,” may reflect limited education or access to schooling. But literacy also varied by gender, region, and economic status. For example:

In early colonial America, male literacy rates were often higher than female literacy rates.

Immigrants sometimes arrived literate in their native language but struggled with English.

Access to schools differed dramatically between rural and urban families.

When we encounter literacy markers in our research, they give us a window into the educational opportunities—or barriers—our ancestors faced.

Deciphering Handwriting: Genealogy’s Penmanship Class

If you’ve ever squinted at a census page, trying to tell whether a name reads Miller or Millar, you’ve already had your first lesson in historical handwriting. Styles of penmanship shifted over centuries, and clerks often used flourishes or abbreviations unfamiliar to modern eyes.

Some practical strategies for tackling tricky handwriting include:

Compare letters across the page. How does the clerk write other “s” or “r” letters?

Use context clues. If the family lived in Smithfield, that smudged name is probably “Smith.”

Familiarize yourself with old scripts. Online tutorials in paleography (study of old handwriting) can be invaluable.

This challenge may feel like being back in grade school, slowly sounding out words again. But patience often reveals details that would otherwise be missed.

Documents as Lessons in Reading

When we read old records, we’re not just extracting facts—we’re learning to “read between the lines.” Some examples:

Letters and diaries reveal not just events but emotions, relationships, and cultural attitudes.

School records show grades, attendance, and sometimes even teacher comments, offering a glimpse of a child’s daily life.

Church registers often preserve notes in Latin or older forms of English, requiring extra study to interpret.

Legal documents like wills or deeds contain phrasing rooted in centuries-old law.

Reading these requires us to revisit skills of close reading—just like analyzing a passage in literature class.

Interpreting Language and Terminology

Words change over time. A “consumption” diagnosis in the 1800s meant tuberculosis, not overeating. “Spinster” in a marriage record may simply mean “unmarried woman,” not a negative label. Interpreting terms accurately is essential to avoid modern assumptions.

Building a personal glossary of archaic terms you encounter is a useful genealogical practice. Think of it as your own family history dictionary—one that makes old texts feel more approachable.

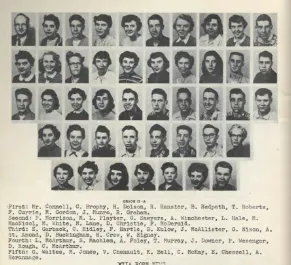

School Registers: Our Ancestors as Students

Some of the most charming records are school registers, if you can find them. They may include:

Names of pupils enrolled

Ages and grade levels

Attendance records (which often reveal farm or labor obligations)

Teacher notes about behavior or performance

These records remind us that our ancestors once sat in desks, much like today’s children, learning their ABCs. Sometimes, these documents also mark the first evidence of literacy in a family line.

Practical Tips for Genealogy’s Reading and Writing Lessons

Slow Down: Don’t skim old records—read them as carefully as you would study a passage of classic literature.

Transcribe: Copy documents word-for-word to ensure accuracy. Transcribing sharpens your eye for detail.

Annotate: Like a student writing notes in the margin, jot down interpretations and questions.

Use Modern Tools: Magnification apps, handwriting reference guides, and digital archives can make deciphering easier.

Collaborate: Share difficult documents with genealogy groups; sometimes fresh eyes see what we miss.

Leverage AI Tools: Artificial intelligence can assist in transcribing old handwriting, enhancing faded text, and even identifying unfamiliar terminology. AI-powered transcription and image enhancement tools can save time and increase accuracy, making tricky documents more accessible than ever.

Family Stories Preserved in Writing

The most precious finds are often handwritten letters, recipe cards, or diaries. These connect us directly to the person who held the pen. A grandmother’s handwriting on a recipe for bread isn’t just ink—it’s an inheritance of memory and tradition.

Encouraging family members to write their own stories today can continue that chain. Just as past generations left us their words, we can leave ours for the future.

Homework: A Genealogy Writing Exercise

To carry this classroom theme forward, here’s your “assignment”:

Choose one handwritten document from your collection.

Transcribe it word-for-word.

Note down any unusual words or phrases.

Reflect: What does this document tell you about the writer’s education, values, or daily life?

Completing this exercise will sharpen your skills and deepen your understanding of your ancestor’s world.

Conclusion

Reading and writing are more than school subjects; they are bridges across time. Through literacy—or its absence—our ancestors revealed who they were, how they lived, and what opportunities they had. Every document, whether neatly written or barely legible, is part of the ongoing dialogue between past and present. In genealogy’s classroom, we become both students and storytellers, learning to read our ancestors’ world while writing our family’s history anew.