Journeys to Freedom: Using Records to Trace African American Ancestors Beyond Juneteenth

Journeys to Freedom: Using Records to Trace African American Ancestors Beyond Juneteenth

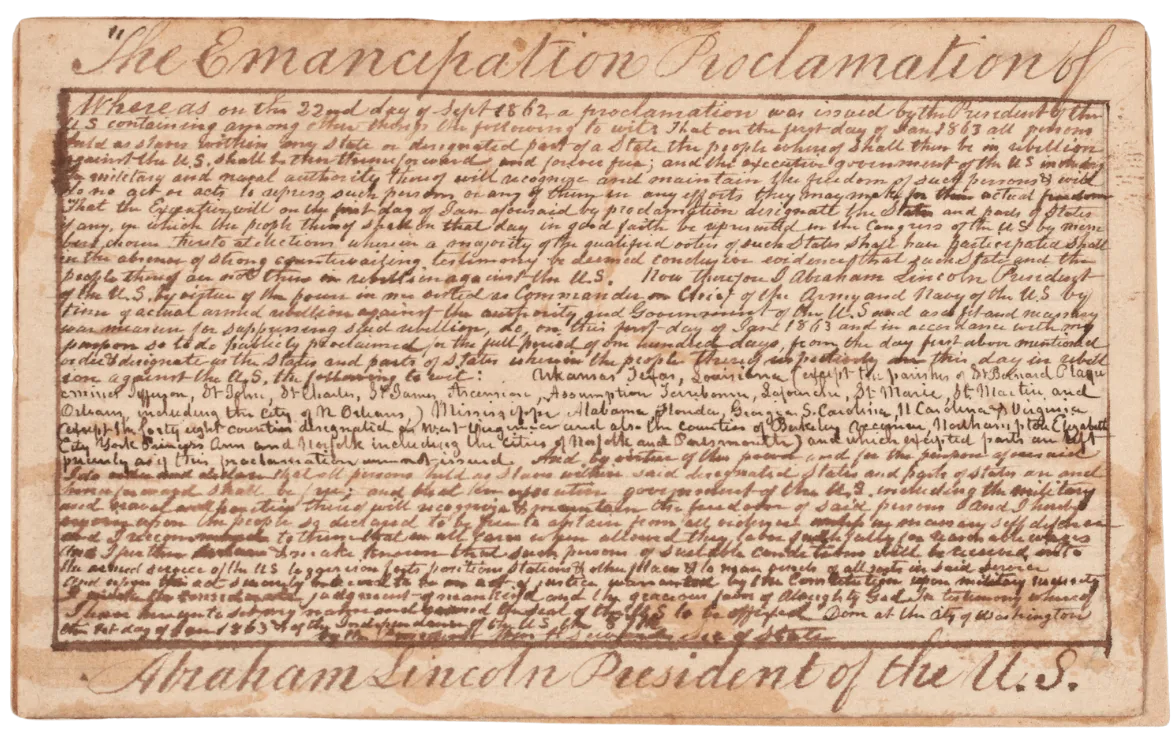

Juneteenth—celebrated annually on June 19—marks a turning point in American history and in African American family history. On this date in 1865, Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, and declared that all enslaved individuals were free, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. For genealogists, Juneteenth symbolizes more than a legal shift; it represents a profound change in how African American ancestors began to appear in records—not as property or statistics, but as named individuals.

This transition opens doors to a rich, though often complex, journey of discovery. Tracing African American ancestry before and after emancipation requires both patience and perseverance. It involves navigating a fragmented historical landscape and reclaiming stories long buried in ledgers, inventories, and whispers passed down through generations.

My own family lore speaks to this resilience. According to stories passed down through the generations, my great-aunt married a man who had escaped slavery in the American South. He fled northward on foot and in secret, ultimately crossing into Canada through Ohio on the Underground Railroad. Their union was a quiet, powerful testament to endurance and new beginnings. Though we have yet to uncover his name in records, his story fuels our family's ongoing journey into the past.

The Challenge of Early Records

Before emancipation, enslaved people were not legally recognized as individuals with full rights. They were recorded as property—listed by age and sex, not by name—in estate inventories, bills of sale, tax documents, and probate records. U.S. Federal Census slave schedules from 1850 and 1860 offer only partial information, identifying the enslaver and enumerating enslaved people by age, gender, and sometimes skin tone.

To find ancestors during this period, genealogists often begin with the records of those who enslaved them. This is not easy work—it can be emotionally taxing and ethically complex. But these documents often provide the only trail to the names and lives of those once rendered invisible.

Following the Paper Trail: Pre-Emancipation Strategies

Start with the 1870 Federal Census—the first where formerly enslaved African Americans were recorded by name. Use it as an anchor. Work backward, focusing on location, approximate age, and familial relationships. Look for neighbors with similar surnames or shared households. Clusters of families often remained near one another after emancipation.

From there, identify likely enslavers in the same county or parish. Land deeds, probate records, and wills are especially useful. If your ancestor took the surname of a former enslaver, it may lead you directly to that family’s papers.

Church records also hold value. African American congregations were often founded immediately after emancipation, and early church records can contain baptisms, marriages, and even notes about community status or migration.

Post-Emancipation Progress: New Kinds of Records

After 1865, formerly enslaved people began to appear more regularly in public records. The Freedmen’s Bureau (formally the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands) was created to assist with the transition from slavery to freedom. Between 1865 and 1872, it generated a wealth of records:

Labor contracts that defined employment terms between former enslavers and freed people.

Marriage records, legitimizing unions previously unrecognized under slavery.

Education reports, listing teachers and students.

Medical records, including hospitals, vaccination programs, and patient logs.

Some of the most poignant records are the Freedmen’s Bureau’s letters and personal testimonies, which offer a rare, intimate look into the lives of newly freed individuals.

The Freedman’s Bank, established in 1865, also created detailed depositor records. Many include family relationships, birthplaces, employers, and even physical descriptions.

The North Star Beckons: Escaping to Freedom

Stories like the one in my family, where a man escaped bondage and found refuge in Canada, are echoed in many African American families. The Underground Railroad—a clandestine network of safe houses, guides, and abolitionists—helped thousands escape to freedom. Many travelled north through Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York before crossing into Canada via Detroit, Niagara Falls, or Buffalo.

Once in Canada, formerly enslaved individuals settled in communities like Buxton, Dresden, and Owen Sound in Ontario. Canadian censuses, land petitions, and church registers in these areas often list new arrivals. If you believe your ancestor made such a journey, search Canadian records as part of your research. The 1851, 1855 and 1861 censuses in Canada West (now Ontario) are particularly helpful.

Personalizing the Search: Telling Their Stories

Genealogy isn’t just about names and dates. It’s about storytelling—about reclaiming voices and understanding context. Take time to imagine what life was like for your ancestors. Did they build a church or help start a school? Were they landowners, sharecroppers, or railroad workers?

Photographs, oral histories, and heirlooms breathe life into records. Even if you don’t have a photograph, ask relatives what your ancestors were like. Did they sing spirituals? Cook certain dishes? Celebrate in a particular way? These memories form part of the mosaic.

In my family, the story of the man who crossed into Ontario still shapes our sense of identity. Though his name was never written down in our records, we know he settled in a small town, built a life, and raised children who knew freedom from birth. That story, passed from mouth to mouth, taught us the value of perseverance and quiet courage.

DNA as a Modern Tool

Today, genetic genealogy can offer clues when the paper trail runs cold. Autosomal DNA testing can help identify distant cousins, some of whom may have better-documented lines. Shared matches can suggest common ancestors or migration routes.

For African American research, Y-DNA (for paternal lines) and mitochondrial DNA (for maternal lines) can also help illuminate ancestral origins. While these tests can’t erase the harm done by lost records, they can begin to rebuild lost connections—sometimes across continents.

Many testing companies also estimate African ethnic origins, offering a broader sense of ancestral homeland. While not definitive, it can be powerful to see regions in West Africa highlighted in your DNA profile—a tangible, scientific link to heritage.

Community and Collaboration

African American genealogy is deeply collaborative. There are numerous online groups, local historical societies, and national organizations dedicated to supporting Black family historians. Initiatives like the Beyond Kin Project and the Freedmen’s Bureau Transcription Project help uncover and share records that benefit the broader community.

In your own journey, consider sharing what you find. Upload family trees to public sites, contribute to local archives, or donate copies of oral histories. Each piece you share adds to the collective narrative.

Honouring Legacy Beyond Juneteenth

Juneteenth may mark freedom’s arrival, but the genealogical journey extends far beyond. Tracing African American ancestors is both an act of recovery and resistance. It’s about restoring names, remembering love, and honouring struggle.

When we research the lives of those who were once denied freedom, we affirm their humanity. We give voice to the silenced and dignity to those whose stories were lost in the margins.

In my family, the tale of a man escaping slavery and marrying my great-aunt is not just lore—it’s a legacy. Whether or not we find his name, we carry his story forward. That, too, is genealogy. That, too, is Juneteenth.